LIVING IN THE WORK: SEPTEMBER 2022

Before you read any further, please know that this month’s essay includes examples of suicide. If you’re not comfortable going forward please reach out to me at wileycashauthor@gmail.com, and we’ll come up with another way for this month’s page to serve you. This month, we’re focusing on the conversation between memory and fact, which was partly inspired by a book I recently read and this month’s Creator’s Conversation with Scott Simon, the iconic host of NPR’s Weekend Edition. You might not know Scott Simon’s name, but when you watch our interview you will definitely recognize his voice. Something he said during our chat has stuck with me: when he’s interviewing someone for the show, whether it’s the president or a farmer, he’s engaged in the conversation in much the same way he’s engaged in the conversation with the page when he’s writing fiction or memoir. He’s listening closely for what the other is revealing so that he can ask the right questions in response. I want us all to bring that act of listening to the conversation, whether it’s between memory and fact or between our art and ourselves, to everything we do in September. In this month’s edition of Living in the Work you’ll find a couple of new features. Beneath our exercise assignments you’ll find a link where you can share your work with me and other members, and we’ll be able to share comments of our own. There’s a similar conversation feature available beneath the discussion questions for this month’s book club selection. I’d love to see and comment on both your creative work and your thoughts on The Kindest Lie. Let’s support one another with insightful, kind comments and get some real conversations going. There’s also been a slight change to how our virtual book club discussions will be run. These meetings, which I’m calling “Coffee, Cocktails, Craft,” will now be geared toward larger discussions of creativity and craft, and while I’ll be referencing the book club selection, especially in my craft conversations, reading the book won’t be necessary to join us. I hope you all have a great September living in the work!

“The Conversation Between Memory and Fact”

There was a field behind the house I grew up in in Gastonia, North Carolina, and it ran for a mile or more before turning into forest before the forest opened up to reveal the golf course of the Gaston County Country Club. If you were standing in our backyard, there were dense woods on the left side of the field, and on the right side were more woods, where a stream ran through a clearing. My brother and I and our neighborhood friends spent hours and hours in those woods and in the field, doing everything from building clubhouses to shooting BB guns to making trails in the high brush with long sticks we unironically called “whackers.”

If I take a moment to create space for my memories, dozens of them flood into my mind: the tunnels of fallen trees that we called Halloween Hollow; the time I caught a hammer’s claw just above my left eyebrow when a friend and I were hammering boards onto a tree to make a ladder; the woods and field being cleared for a new neighborhood just as we, mercifully, had grown old enough not to mourn the ending of the innocence and joy of our childhoods.

But we lived in the South so surely something Gothic lurked in those woods and in that field. Surely there was something out there that could not be explained, neither by the heart of a child nor the mind of a grown man looking back. Surely Flannery O’Connor’s Misfit or Faulkner’s Miss Emily made an appearance, right?

I can remember being on the screened porch that our father built one day when I saw police lights flashing through the trees in our backyard. The field behind our house had been cleared by this time, and it looked like something was going on in an empty cul-de-sac where the wooden bones of new houses were just beginning to rise. I can’t remember whether or not I was alone, and I can’t remember whether or not I heard a gunshot. But I do remember going out into the field later that evening after the police had left and their lights were no longer flashing. At the end of the cul-de-sac, in a cleared space surrounded by tall grass and weeds, lay clumps of what looked to be brain matter with a tail of blood splatter trailing out beside it. I can remember that the blood was fresh and shiny. I can also remember taking other people back there to see it, not only that night, but for the next couple of days before the blood dried up and there was no discernible difference between it and the earth.

A few days ago, my brother Cliff, who’s almost three years younger than me, was visiting, and we were sitting in the living room talking about our neighborhood back in Gastonia, which my parents left in the summer of 1998 when they moved down to Oak Island. If you’ve read When Ghosts Come Home you know this is where that novel is set. Anyway, I brought up the story of the man being shot in the cul-de-sac of the new neighborhood behind our house, and I told Cliff that somehow I knew that the man had robbed a bank up on Union Road and driven his car into the woods trying to escape police. When his car could go no farther, he climbed out and fled on foot. He shot himself once he realized he was cornered.

But Cliff remembered it differently. According to him, the person who shot himself hadn’t been a bank robber because there hadn’t been a bank robbery. The person who shot himself was a troubled young man a few years older than us who grew up in our neighborhood. But I knew that story wasn’t correct because the young man in question had committed suicide by hanging himself in the woods behind someone else’s house, not by shooting himself in the woods behind ours. We kept talking about it, hashing out various scenarios, but we could never agree on exactly what happened, nor could we agree on to whom it had happened. Soon, our memories began to merge, and the ready outline of fact, what little fact we’d been able to retain, was lost.

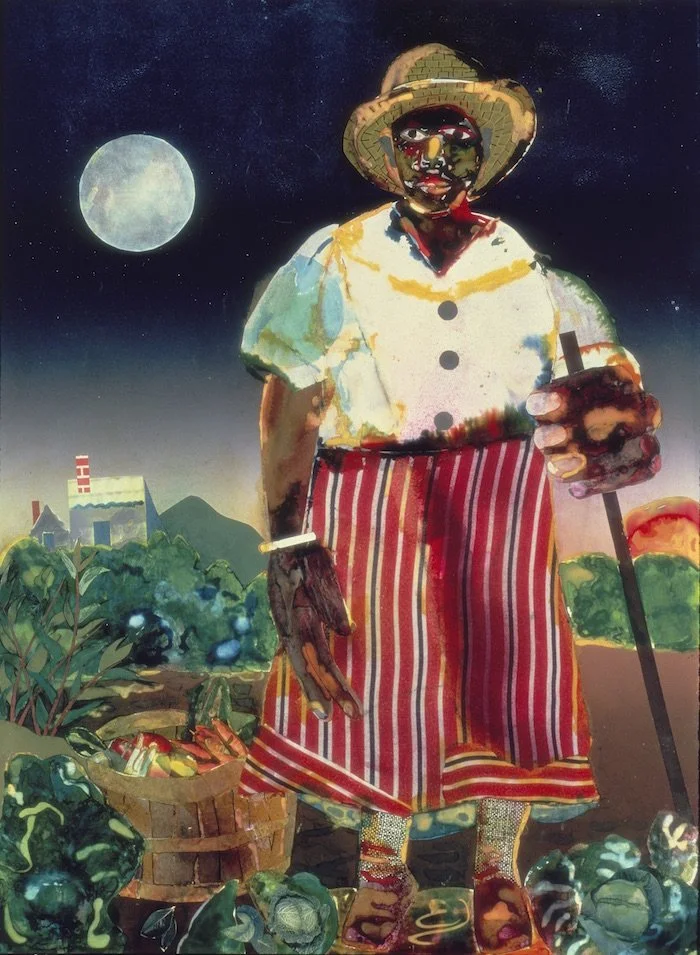

The experience reminded me of a book I recently reviewed for The Assembly called Romare Bearden in the Homeland of His Imagination: An Artist’s Reckoning with the South by Brenda Elizabeth Gilmore. In the book, Gilmore writes about how Bearden, who was an iconic artist during the twentieth century best known for his collage work, often filled in the gaps in his memory with creativity. One of the best examples of this is in a series of collages Bearden based on his memories of an elderly woman Maudell Sleet who farmed a plot of land in what is now downtown Charlotte in the early 1900s when Bearden was a young boy. Bearden recalled that the woman was old and powerful, and he’d heard stories about the ghost of her husband haunting the garden. In reality, no one named Maudell Sleet ever lived in Charlotte. But there was a young woman named Maude Morgan who found herself pregnant at seventeen and married Walter Slade, whose mother farmed a garden near the Bearden family home, where Maude’s mother-in-law probably put her son’s new wife to work. The marriage was soon rocked by Walter’s infidelity, and eventually he left for Washington D.C. with his mother and father, perhaps leaving Maude behind to work the garden alone. At the time, men who abandoned their wives were known as ghost husbands, so perhaps this is where Bearden’s memory of Maudell’s husband haunting the garden was born.

While the story of Maudell Sleet might not be true in the history of Charlotte, the story is certainly true in Bearden’s work, and that is where it lives on. It is impossible that both my and Cliff’s version of events are true, but both versions now live, and over the years I imagine they will become entangled with one another, and perhaps the stories will change.

When I was in graduate school in Louisiana, the writer-in-residence who replaced Ernest J. Gaines after he retired was named Rikki Ducornet. While I didn’t have the chance to study under Rikki, several of my friends did, and they told me about some writing advice she shared with them that I’ve never forgotten. She suggested that writers consider drawing from two separate spaces from their childhood: the space that scared them and the space that made them feel safe. I think about this often, both the safe places and the scary ones. The memory I have of my grandfather holding my hand while a neighbor’s goat nuzzles my fingers and eats a crabapple from my palm. The quiet, dark room where my uncle would sit during family gatherings after he got too drunk to be around the rest of the family without anyone becoming unnerved. The woods and the field that are no longer behind the house that my family no longer owns, where the lightest and darkest moments of my childhood still live, tangled up in memory and fact.

Exercise #1

Get out a clean sheet of paper and make a map of the place where you grew up. I’m serious. Go ahead. It doesn’t matter if you were raised in the country or in an apartment complex in the city. Map out what you remember. Where did you play? Where did you get hurt? Where did you hide? Where were you not supposed to go? Where did your friends live? Where were the places that scared you? Mark all of these places on your map.

Exercise #2

Sit with your map for a bit. Are any memories being conjured? Are any stories coming to light? Is anything surprising you? Can you readily discern the difference between your memories and fact? Does it matter? For this exercise, the answer is no. I want you to write a story of one of your memories. What happened? Who was there? What did it mean? How does the gauze of time affect the narrative?

Want to share your work with other members?

This month we have a new feature that allows us to share and comment on one another’s work in real time. Want to share your exercise responses with me and other members? Want a little feedback from a supportive group? Click here to share and read the work of others.

CREATORS’ CONVERSATION: SCOTT SIMON

THE AUGUST SELECTION OF THE OPEN CANON BOOK CLUB

The Kindest Lie by Nancy Johnson

Every family has its secrets...

It's 2008, and the inauguration of President Barack Obama ushers in a new kind of hope. In Chicago, Ruth Tuttle, an Ivy-League educated Black engineer, is married to a kind and successful man. He's eager to start a family, but Ruth is uncertain. She has never gotten over the baby she gave birth to--and was forced to leave behind--when she was a teenager. She had promised her family she'd never look back, but Ruth knows that to move forward, she must make peace with the past.

Returning home, Ruth discovers the Indiana factory town of her youth is plagued by unemployment, racism, and despair. As she begins digging into the past, she unexpectedly befriends Midnight, a young white boy who is also adrift and looking for connection. Just as Ruth is about to uncover a burning secret her family desperately wants to keep hidden, a heart-stopping incident strains the town's already searing racial tensions, sending Ruth and Midnight on a collision course that could upend both their lives.

Powerful and unforgettable, The Kindest Lie is the story of an American family and reveals the secrets we keep and the promises we make to protect one another.

A native of Chicago’s South Side, Nancy Johnson worked for more than a decade as an Emmy-nominated, award-winning television journalist at CBS and ABC affiliates nationwide. A graduate of Northwestern University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, she lives in downtown Chicago and manages brand communications for a large nonprofit. The Kindest Lie is her first book.

Click this link for 10% off and free shipping from Ghost Hill Press. Please remember to use the code OPENCANON at check out for free shipping.

Click this link to join Wiley for the new “Coffee, Cocktail, Craft” on Sunday, September 25 at 8:00 p.m. EST. We’ll talk about creativity and craft, specifically examples from the book club selection. There’s no requirement to have read or finished the book to join us!

WILEY’S READING GUIDE & DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

This novel is a little more commercial than the previous novels we’ve read, including Brown Girls and The Five Wounds. Most often, commercial fiction is driven by plot, while literary fiction is driven by character. How would you delineate those distinctions across these three books?

The election of Barack Obama was a pivotal moment for many Americans of all races and backgrounds, bringing hope to millions who’d felt left out of the political process. Why does Johnson choose to open the novel against the backdrop of his election?

Ruth nurses a long-held secret from her husband Xavier. How does this central tension open up other tensions in the novel? How does Johnson make use of these tensions?

There are several examples of menace at work in the novel. How does Johnson keep the characters from ever feeling truly settled? How does that affect your reading experience?

Butch is clearly portrayed as a racist, but Johnson keeps him from being a flat character defined by a single, repulsive trait. How does she accomplish this?

Midnight is a character who appears to the reader very differently than he appears to many of the characters in the novel. How does Johnson achieve these varying perceptions of a single character?

How does race affect how different characters process and respond to similar experiences?

Mama is a very complicated character, and she’s capable of surprising us, especially when Ruth discovers her overnight friend upon first arriving home. How else did Mama surprise you?

How does toxic masculinity affect the men in the novel? How are they reaching for an ideal that’s harmful? Can you bring Amadeo from The Five Wounds into this consideration?

How does Johnson advance conversations around race, class, and gender in the novel?

Do you want to discuss these questions and any others you might have with me and other members of the group? This month features a new opportunity for us to discuss the Open Canon selection with one another in real time, while also commenting on the thoughts and questions of other members. Click here to share your thoughts on The Kindest Lie.

IF YOU LOVED THE KINDEST LIE…

Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison

Milkman Dead was born shortly after a neighborhood eccentric hurled himself off a rooftop in a vain attempt at flight. For the rest of his life he, too, will be trying to fly. As Morrison follows Milkman from his rustbelt city to the place of his family’s origins, she introduces an entire cast of strivers and seeresses, liars and assassins, the inhabitants of a fully realized Black world.

You Remind Me of Me by Dan Chaon

You Remind Me of Me begins with a series of separate incidents: In 1977, a little boy is savagely attacked by his mother’s pet Doberman; in 1997 another little boy disappears from his grandmother’s backyard on a sunny summer morning; in 1966, a pregnant teenager admits herself to a maternity home, with the intention of giving her child up for adoption; in 1991, a young man drifts toward a career as a drug dealer, even as he hopes for something better. With penetrating insight and a deep devotion to his characters, Dan Chaon explores the secret connections that irrevocably link them. In the process he examines questions of identity, fate, and circumstance: Why do we become the people that we become? How do we end up stuck in lives that we never wanted? And can we change the course of what seems inevitable?

The Deep End of the Ocean by Jacquelyn Mitchard

Few first novels receive the kind of attention and acclaim showered on this powerful story—a nationwide bestseller, a critical success, and the first title chosen for Oprah’s Book Club. Both highly suspenseful and deeply moving, The Deep End of the Ocean imagines every mother’s worst nightmare—the disappearance of a child—as it explores a family’s struggle to endure, even against extraordinary odds. Filled with compassion, humor, and brilliant observations about the texture of real life, here is a story of rare power, one that will touch readers’ hearts and make them celebrate the emotions that make us all one.

THE SEPTEMBER SELECTION OF THE OPEN CANON BOOK CLUB WILL BE…

Poet and essayist Cathy Park Hong fearlessly and provocatively blends memoir, cultural criticism, and history to expose fresh truths about racialized consciousness in America. Part memoir and part cultural criticism, this collection is vulnerable, humorous, and provocative--and its relentless and riveting pursuit of vital questions around family and friendship, art and politics, identity and individuality, will change the way you think about our world.

Binding these essays together is Hong's theory of "minor feelings." As the daughter of Korean immigrants, Cathy Park Hong grew up steeped in shame, suspicion, and melancholy. She would later understand that these "minor feelings" occur when American optimism contradicts your own reality--when you believe the lies you're told about your own racial identity. Minor feelings are not small, they're dissonant--and in their tension Hong finds the key to the questions that haunt her.

With sly humor and a poet's searching mind, Hong uses her own story as a portal into a deeper examination of racial consciousness in America today. This intimate and devastating book traces her relationship to the English language, to shame and depression, to poetry and female friendship. A radically honest work of art, Minor Feelings forms a portrait of one Asian American psyche--and of a writer's search to both uncover and speak the truth.

Click this link to order Minor Feelings from Ghost Hill Press, where you’ll get 10% off. Please use the code OPENCANON at checkout to get free shipping from Ghost Hill Press, my neighborhood independent bookstore!

Cathy Park Hong is the author of Translating Mo'um and Dance Dance Revolution and has won a Pushcart Prize and the Barnard Women Poets Prize. She lives in New York and teaches at Sarah Lawrence College.